Three-Point vs Four-Point Bending: What’s the Real Difference?

Bending tests are among the most widely used mechanical tests in materials and structural evaluation. The basic idea is straightforward: a specimen is supported at two points, a load is applied, and the resulting force–deflection response is used to calculate flexural strength and stiffness.

Despite this apparent simplicity, the way the load is applied has a significant impact on stress distribution, failure behavior, and the meaning of the measured values. The most common approaches, three-point and four-point bending, are often treated as interchangeable. In reality, they answer subtly different questions about material behavior.

What Three-Point and Four-Point Bending Have in Common

In both methods, the specimen behaves like a beam under bending. The upper surface experiences compressive stress, while the lower surface is subjected to tensile stress. Failure typically initiates on the tensile side, where materials are generally less tolerant to defects and microstructural variations.

Both tests are used to extract flexural strength, flexural modulus, and load–deflection characteristics. From a control and measurement perspective, the machine records applied force and displacement, from which stress and strain are derived using beam theory assumptions. The main distinction lies not in what is measured, but in how the internal stresses develop within the specimen.

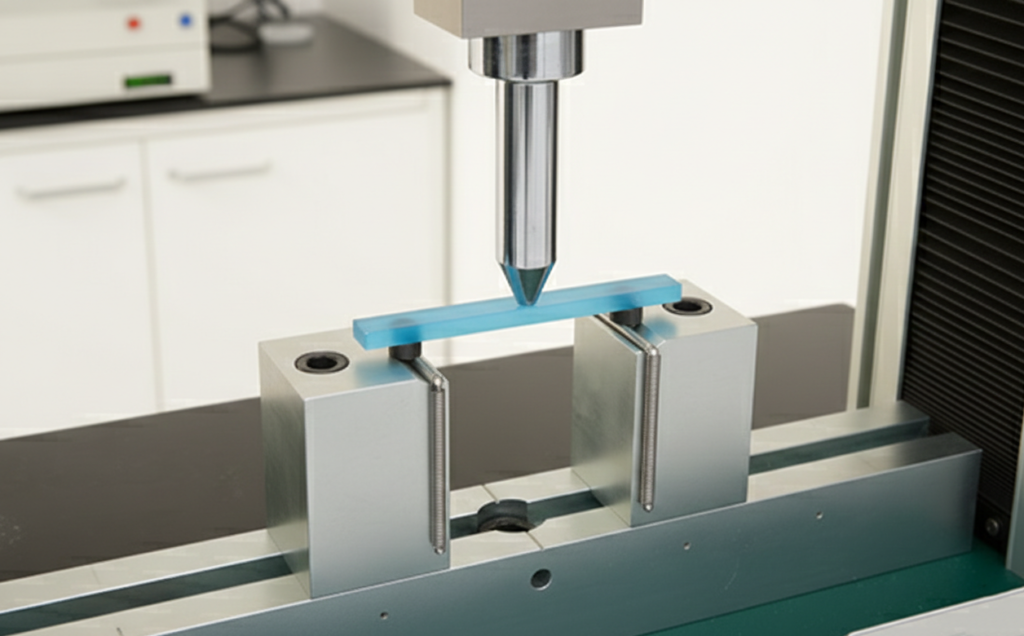

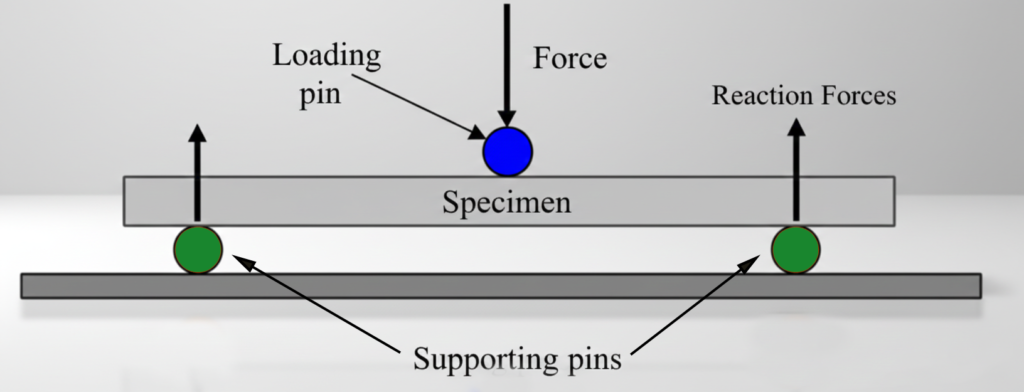

Three-Point Bending: Localized Maximum Stress

In three-point bending, the load is applied at a single point, usually at mid-span. This creates a bending moment that reaches its maximum directly under the loading nose.

Key characteristics:

- Maximum stress is concentrated at one location

- Failure typically occurs under the loading point

- Results are sensitive to:

- surface finish

- local defects

- load nose geometry

- alignment accuracy

Because the highly stressed region is small, three-point bending often reflects the behavior of the weakest local section rather than the overall material volume.

Due to its simplicity, three-point bending is commonly used for routine testing, quality control, and brittle or relatively homogeneous materials. It is fast to set up, requires fewer alignment steps, and typically produces a clearly defined fracture location.

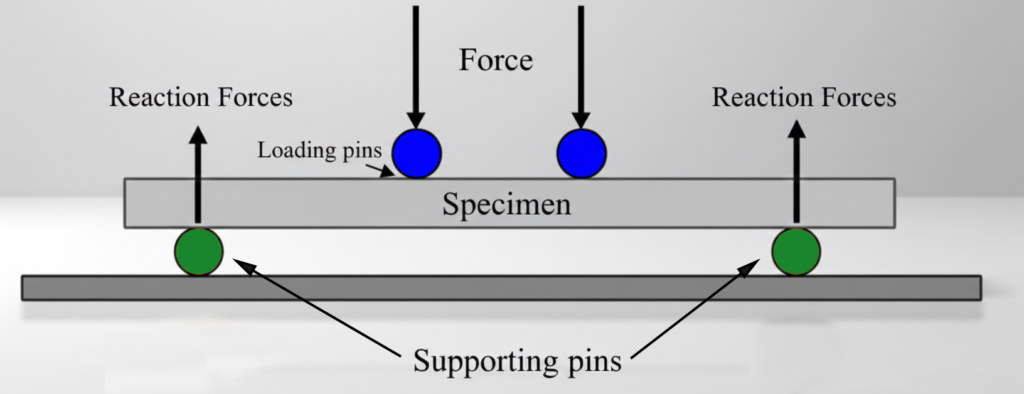

Four-Point Bending: Uniform Stress Over a Region

Four-point bending introduces two loading points. Between them, the bending moment is constant, creating a region of uniform maximum stress.

Key characteristics:

- A larger portion of the specimen is equally stressed

- Failure can occur anywhere between the load points

- Local surface defects have less influence on results

- Measured properties better represent bulk material behavior

This makes four-point bending especially useful for:

- composites and fiber-reinforced materials

- wood and concrete

- anisotropic or layered structures

- research and design validation

The trade-off is increased fixture complexity and higher sensitivity to load symmetry and alignment.

Stress Distribution and Why It Matters

The fundamental difference between the two methods lies in the bending moment profile. In three-point bending, the moment peaks at a single point. In four-point bending, it forms a plateau.

This difference has practical consequences. When only a small region is highly stressed, as in three-point bending, results are more sensitive to surface condition and local geometry. When a larger region is stressed, as in four-point bending, the test is more likely to capture the intrinsic behavior of the material rather than an isolated defect.

This is why four-point bending often yields slightly lower flexural strength values. More material is subjected to critical stress, increasing the probability that a flaw will govern failure. The result is not less accurate; it is just more conservative and often more realistic for structural applications.

Effects on Measured Strength and Modulus

Flexural strength obtained from three-point bending is frequently higher than that from four-point bending, even for identical specimens. The difference typically reflects the stress volume effect rather than experimental error.

For stiffness measurements, four-point bending tends to produce more stable modulus values. The absence of a sharp stress peak and the reduced influence of shear deformation improve the reliability of elastic measurements, especially when deflection is measured directly on the specimen.

In contrast, three-point bending can still provide valid modulus data, but results are more sensitive to span length, specimen thickness, and how displacement is measured.

Practical Selection Guidelines

In practice, the choice depends on the goal of the test:

- For speed, simplicity, and routine checks → three-point bending

- For material comparison, validation, and structural relevance → four-point bending

- When standards specify the method → follow the standard

- When repeatability across labs matters → four-point bending is usually safer

Software and Control: Where Test Method Meets the Machine

While fixtures define the mechanical loading condition, the control system and software largely determine how accurately that condition is applied.

Bending tests, particularly four-point and cyclic tests, require:

- stable closed-loop force or displacement control

- symmetric load application

- consistent timing and data acquisition

- precise definition of ramps, dwells, and waveforms

A software-defined control platform such as TACTUN helps address these needs by allowing bending tests to be defined as configurable workflows rather than hard-coded programs.

In practice, this enables:

- easy switching between three-point and four-point bending on the same machine

- parameterized test definitions (span, control mode, rate, dwell)

- consistent execution across machines and labs

- support for advanced tests such as cyclic or fatigue bending

By separating test logic from hardware-specific implementation, platforms like TACTUN improve transparency and repeatability—allowing engineers and operators to focus on interpreting material behavior rather than compensating for control limitations.

Share this post: